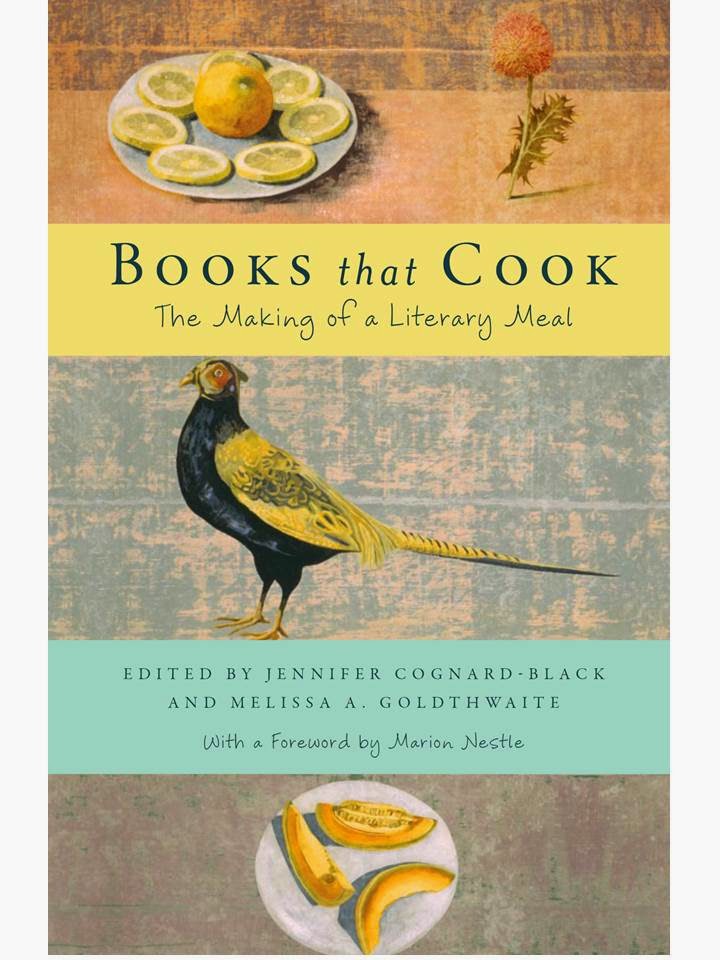

Books that Cook: An Interview with Melissa Goldthwaite

Organized in menu sequence from starters to dessert, Books that Cook features an impressive range of contributors

from the culinary world—Julia Child, Fannie Merritt Farmer, James

Beard, Alice Waters—and from the world of letters—Maya Angelou, Sherman Alexie,

Nora Ephron...and many others. Co-editors Jennifer

Cognard-Black and Melissa Goldthwaite introduce each “course” with an essay putting it in historical context.

Tomorrow at Washington D.C.'s fabulous indie bookstore Politics and Prose, Melissa and Jennifer (and a panel of writers including yours truly) will be celebrating Books That Cook. And today

Melissa lets me ask her some questions about this delicious project.

I’d love to hear about

the genesis of this project.

In the late ‘90s, I started collecting books—novels, memoirs,

essay collections—in which the authors had embedded recipes. One evening, I was

standing in a bookstore in Ohio with Jennifer Cognard-Black, and I said,

“Someday, I want to teach a class in which all the books include recipes.” That

comment started a conversation that has lasted nearly fifteen years—and

continues. Every time we talked or visited one another, we were sharing book

recommendations and sometimes recipes. In autumn of 2003, Jennifer and I each

taught our first versions of a class we called Books that Cook, and a couple

years later, conversing in her kitchen in Maryland, we decided to work on a

book together. We started sending the book proposal to potential publishers in

April of 2007. Seven years later, the book is finally out.

How does your teaching

feed your writing and research? And how do writing and research feed your

teaching?

Books That Cook started with personal

reading and conservation and moved to the classroom and then to a wider

audience, and it will return to the classroom.

Much of my research is pedagogical, so there’s a direct link

between my teaching and research. When I’m choosing readings for an anthology,

for example, I always think not only about the particular piece but also how it

will work in the classroom. I sometimes include readings I’m thinking about for

a book in a course packet to see how students respond.

I try at least a couple times a year, though, to read a book

that I have no intention of teaching or writing about because I read

differently when I’m going to teach something or write about it in a scholarly

way. There’s a different kind of joy that comes from reading just to read. I have

to practice that kind of reading.

In terms of creative writing, when I give an exercise in class,

I often write while students are writing and take my turn sharing what I wrote.

And, of course, reading is a great inspiration for writing as well.

|

| All food photos are by Melissa Goldthwaite |

It’s sensory: scents, textures, shapes, colors, tastes. People

also often have powerful memories of and strong feelings about food—both

positive and negative. Most people have some memory of being forced to eat

something as a child, or they remember the excitement mixed with nervousness of

a first dinner date or party or, perhaps, the embarrassment of spilling

something. The foods and situations are different, but the feelings and

experiences are similar, providing common ground.

What a character eats or doesn’t eat can also reveal something

about that person or a relationship. For example, in Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe, Fannie Flagg shows

Evelyn Couch’s sense of self and her developing friendship with Mrs.

Threadgoode through food. Although Evelyn eats processed junk food alone early

in the book, as her friendship with Mrs. Threadgoode develops, she begins to

see herself differently and begins to eat and share more nourishing foods.

Tables are also places of conversation, so they provide a

perfect setting for dialogue and body language and description. If I’m working

with a writer who has difficulty including sensory details, I can say, “Write

about a holiday dinner,” and the details start to come. These ritual meals are

often good starting places for writing about food.

Books That Cook is impressively ambitious and wide-ranging. What

were some of the challenges of pulling it together?

One of the biggest challenges of this book was permissions

costs. Our first table of contents was organized historically, and it was much

longer. Even once we changed the organization and cut drastically, there were

pieces we couldn’t include because of high fees.

We also wanted at least one poem, essay, and piece of fiction in

each chapter. It wasn’t difficult to find nonfiction—much literary writing

about food is nonfiction. But there are fewer short stories that embed recipes.

There are, however, many fine novels. Still, it’s difficult to excerpt from a

novel, so that was definitely a challenge.

I’m particularly intrigued that you included a selection from the Alice B. Toklas Cookbook. Toklas is such an interesting bridge between the literary and culinary worlds. Can you say something about the choice to include her work here?

Toklas called her book a “mingling of recipe and reminiscence,”

which is a fitting description. Jennifer and I were interested in including a

range of literary writing about food that embedded recipes in different ways.

Toklas moves from reminiscence to recipe and back again, sometimes introducing

a fully formed recipe in the middle of writing about a particular memory.

She’ll be in the middle of a sentence, then there will be a space, the dish

title, then a recipe written in paragraph form. She had a writer’s eye for

detail and description about food and culture (especially differences between

French and American cultures). And she showed the connections among the life of

the mind, the preparation and sharing of food, and the importance of spending

time with friends.

I’m also wondering if

you would say a bit about that selection’s final paragraph, in which a friend

asks, “with no little alarm, But, Alice, have you ever tried to write. As

if a cook-book had anything to do with writing.”? I’m tantalized by that

last sentence. What do cookbooks have to do with writing?

Cookbooks have everything to do with writing. Cookbook writers

have to be attentive to detail, extraordinarily precise—and simultaneously

creative, even as they take into account histories and received practices.

Later this month, I’ll be doing a reading and cooking

demonstration at the Baltimore Book Festival. In preparation (so samples can be

made for the audience), I had to describe in detail how to make the dish I would be making. I had to put what comes

somewhat naturally into words—with measurements and step-by-step instructions.

And then I had to list exactly what I’ll need on stage. I’m terrible at this

last part. I asked for—among other supplies—“a large, sharp chef’s knife” when

I should have been far more specific. Who knows what I’ll end up with. . . . I

just hope I come back with all my fingers.

Anyone who has written a cookbook knows the work and the

inventiveness that goes into it—and the understanding of form and audience one

must have. Toklas also had stories to tell: for example, she writes of

preparing a fish for Picasso (and decorating it to amuse him!). She was

surrounded by artists and writers. Surely she knew cooking and writing about it

as art too.

I didn’t start cooking until I was in graduate school, and the

first book I really used was Carol Gelles’s 1,000

Vegetarian Recipes. It’s definitely not a fancy book. Perfect for

beginners. But I loved that book because it taught me the basics—at least of

vegetarian cooking. The ingredients lists were manageable, and I learned how to

add to a recipe or change an ingredient or two without fear of ruining the

entire dish.

I’m sure I have at least a hundred cookbooks now, but I rarely

follow recipes exactly. When I get a new cookbook, I sit down and look through

the entire book, sometimes marking pages with Post-it flags. I go back to the

books for inspiration—a reminder of dishes I’d like to try. But when I try

something new, I look up as many versions as I can find of a similar dish to

see what the common elements are, and then I experiment. I don’t think that

I’ve ever followed a recipe exactly after the first or second time making a

dish.

Have you tried any of

the recipes in Books That Cook? I’d love to hear about it.

I’ve had versions of several dishes in the book, but I haven’t followed

the recipes exactly. Even the recipe for Summer Salad, which I included in my

poem in the book, is different from how I make that dish. Sometimes literary

taste is different from taste in food!

But I have had Howard Dinin’s perfect fried egg sandwich, which

is delicious. When I make my own egg sandwich, though, I add Piment d'Espelette and melt aged cheddar on the bread.

I

tend to remember “firsts” more than meals. I remember the fish and chips

(wrapped in newspaper) I bought at a street cart in London when I was sixteen; it

was the first time I had malt vinegar. I remember the potato croquettes I had

this past summer at a truck stop in Germany. I remember my first Prosecco, my

first Cerignola olive.

I’ve

enjoyed multi-course meals at fine restaurants in France and Switzerland. But

the meal I remember most was from an Indian restaurant in a strip mall in

Columbus, Ohio. The dish was called “shubnub chicken.” It was only my second

time in an Indian restaurant, and this dish was so good that I would later lie

awake at night thinking about it, replaying the taste and texture in my

imagination. For months, I went to Indian restaurants, looking for that dish,

and I couldn’t find it on any other menu. Finally, I described the dish to an

Indian friend. She said “Shubnub” was a girl’s name, so the dish was likely

one-of-a-kind and named after a person, but as I described the taste, she

concluded it was similar to chicken makhani (also known as butter chicken),

which is widely available. It’s comparable to chicken tikka masala, too, but

I’ve never had another “shubnub chicken.” Still, some version of this dish is

my comfort food, the food I crave when I’m tired or cranky—one of the few foods

that always makes me feel better.

|

| Dessert! |

Comments

Post a Comment